The Peter Principle Isn't Just Real, It's Costly

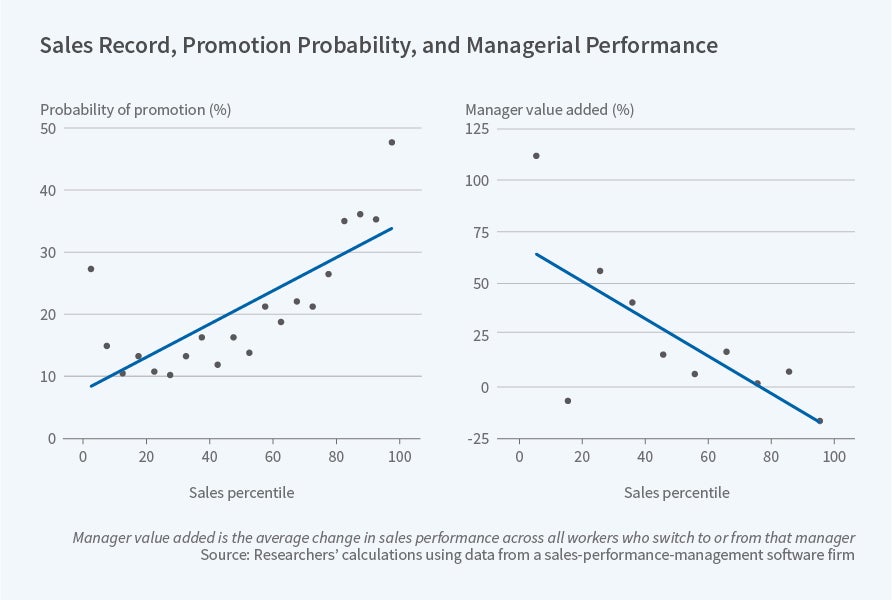

Outstanding sales performance increased the probability that an employee would be promoted, and was associated with sales declines among the new manager's subordinates.

In casual conversations, citing a variation of the Peter Principle — the idea that managers tend to "rise to the level of their incompetence" — often draws a chuckle, especially among those who work for incompetent managers. But in Promotions and the Peter Principle (NBER Working Paper No. 24343) Alan Benson, Danielle Li, and Kelly Shue study employee sales performance and promotion practices at a sample of 214 firms and find evidence that the Peter Principle is real.

The researchers find that the cost of promoting high-performing sales representatives regardless of their comparative managerial potential is actually quite high. Their results suggest that firms either are making bad promotion decisions or have embraced the idea that occasional bad promotions are the price they must pay to keep workers motivated.

First propounded in the 1969 book The Peter Principle: Why Things Always Go Wrong, by Laurence J. Peter and Raymond Hull, this principle has been the source of endless fascination, examination, and humor. Among its primary postulates are that promotion decisions often are based on candidates' performance in current roles, not necessarily on the skills needed in their future management roles, and that the best workers are not always the best candidates for certain management positions.

The current researchers seek to test these hypotheses in a large-scale study of employee performance and promotion decisions. Importantly, their dataset includes information on performance in managerial roles, which makes it possible to study whether some promotions are ultimately costly to firms.

Using data provided by a firm that offers sales performance management software, the researchers obtained access to anonymized records of the companies in the sample and tens of thousands of employees. They observed more than 1,500 employees promoted into management, 156 million sales transactions, and even the work characteristics of those holding jobs, including whether they worked individually or collaboratively. The employees were all in sales in the manufacturing, information technology, and professional-services sectors.

The data suggest that high-performing sales representatives are indeed more likely than other workers to be promoted into management. The doubling of sales credits increases the probability that a salesperson will be promoted by 14.3 percent relative to the base probability of promotion.

The researchers also found that pre-promotion performance data could negatively predict a new manager's value after promotion: A doubling of the new manager's pre-promotion sales was associated with a 7.5 percent decline in the sales performance of each new manager's subordinates.

In another twist, the researchers found that relatively poor prior sales performance among newly promoted managers was associated with significant improvements in their subordinates' performance. This negative correlation is consistent with the view that if firms' promotion policies make it more difficult to be promoted if an employee has poor sales performance, then poor salespeople who are nevertheless promoted should be better managers.

A key observable trait that can help predict which salespeople might make better managers is whether they have experience working within sales teams, rather than individually. The researchers found that, on average, employees with collaboration experience produce better results as managers.

The researchers stress that many firms seem to know that there is a trade-off when promoting top-performing salespeople at the expense of others who might make better managers. The firms accept the cost of weaker management in order to keep a simple and clear incentive structure in place to motivate employees in the sales ranks.

"The trade-off between incentives and match quality is likely to be an important consideration for any firm or institution in which the skills required to succeed at one level in the organizational hierarchy differ from the skills necessary to succeed at a higher level," the researchers conclude.

— Jay Fitzgerald